Some years ago, when exchanges with other countries were viewed favorably, the United States imported a television game show from Holland. The name was changed in transit from “Hunt for Millions” to “Deal or No Deal,” but the concept remained the same. Contestants selected one from a number of briefcases filled with unknown sums of money, and then eliminated the others one by one.

As the contents of each briefcase were revealed, the contestant got a better idea of how much money might be in his or her valise. At each turn, the host would offer a certain amount of money to end the game. Accepting an offer too soon risked missing out on a better outcome. Waiting too long might leave the contestant (sorry for the pun) holding the bag.

It has more than two years since the Brexit vote, and the world is getting anxious about whether there will be a deal, or no deal. Both sides seem to be waiting the other out, hoping for a better outcome. But with key deadlines coming up soon and political unrest on both sides of the negotiation, the possibility that there will be no deal has been rising. That would be an exceptionally costly outcome for all concerned.

The United Kingdom delivered its letter of intent to leave the European Union in March 2017, which set March of next year as the departure date. British Prime Minister Theresa May talked tough at the outset, suggesting that “no deal is better than a bad deal.” Her negotiating team sensed weakness, and expected their counterparts to be anxious for a deal.

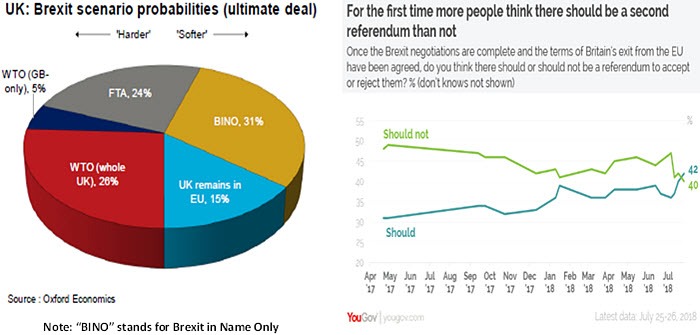

But it has become painfully apparent that Britain did not fully appreciate the complications involved, or the resolve of the EU. As these have been clarified, Brexit remorse has expanded. The sentiment in favor of a new referendum has risen sharply. (Given the complications that would surround a new vote, this remains an unlikely outcome.)

There have been surprisingly few direct negotiating sessions between the two sides. The only major agreement reached was the establishment of a 21-month transition period from the current arrangement to the new one, to avoid any abrupt change of terms. Unfortunately, the transition period only applies if negotiations on all other fronts are concluded successfully.

The time frame for doing so is getting frighteningly short. The outline of a new cooperation was to be ready for the European Council to discuss at its mid-October meeting, but a recent proposal from the U.K. was quickly rejected by the EU. Even if both sides agree to terms, they will have to be approved by the British Parliament. With the Tory party deeply divided over Brexit and the Labor Party waiting opportunistically in the wings, ratification may be a long shot.

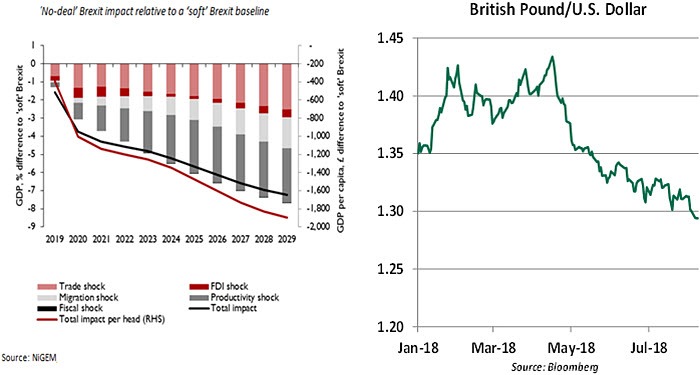

If they fail to reach a deal, the abrupt end to EU membership could have a long series of difficult consequences for Britain:

- The United Kingdom would immediately be removed from trade agreements negotiated by the EU with nothing to replace them. Commerce would be governed by the World Trade Organization, which is struggling with a huge caseload of grievances and dwindling international support.

- The employment status of EU workers in Britain (and vice versa) would fall into limbo.

- A checkpoint would have to be created between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. As we discussed, this would have disastrous economic and political

ramifications. - British service firms, including banks and insurance companies, would be vulnerable to increased restrictions in doing business within the EU.

- The approximately 60 EU regulatory agencies that currently cover commerce in the United Kingdom would immediately have to cease coverage, leaving Britain to fend for itself.

- Shipments of all manner of goods could be held up at the U.K. border. The British government has assembled plans to stockpile medicine, just in case.

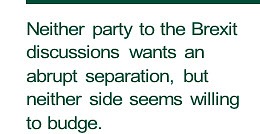

The accumulation of these hindrances would take a substantial toll on the U.K. economy, and the pound, already in retreat, could find itself in free fall.

Neither side is anxious for an abrupt separation. Extending the deadline is certainly possible, but the EU would have to approve the extra time and would probably want concessions for doing so. The stability of the U.K. government is in some question, and the longer negotiations go on, the higher the likelihood of new elections. This would be a setback, as a new government could seek to re-open discussions on entirely different terms.

To a certain extent, the impasse is understandable. Britain was deeply divided over the decision to exit, and its internal politics reflect that. It has been almost impossible to define a negotiating platform that mediates between those who want a clean break and those who have fear of fracture. On the other side, the EU was never going to make exit convenient or costless; this would send the wrong message to other countries who might seek “á la carte” membership.

To a certain extent, the impasse is understandable. Britain was deeply divided over the decision to exit, and its internal politics reflect that. It has been almost impossible to define a negotiating platform that mediates between those who want a clean break and those who have fear of fracture. On the other side, the EU was never going to make exit convenient or costless; this would send the wrong message to other countries who might seek “á la carte” membership.

But the discussions have regressed over the last six months, and the resultant uncertainty has already taken a significant toll. Europe has often come up with economic resolutions at the 11th hour, but as the Brexit clock nears midnight, there is no clear way forward.

Climbers are often cautioned about peering over the cliff’s edge, which can be frightful and disorienting. In the case of Brexit, however, it might be useful for policymakers on both sides to look down into the canyon and appreciate its depth. That might prompt them to step back from the precipice, and back to serious negotiations. No deal would be a very bad deal.

Doing More With Less

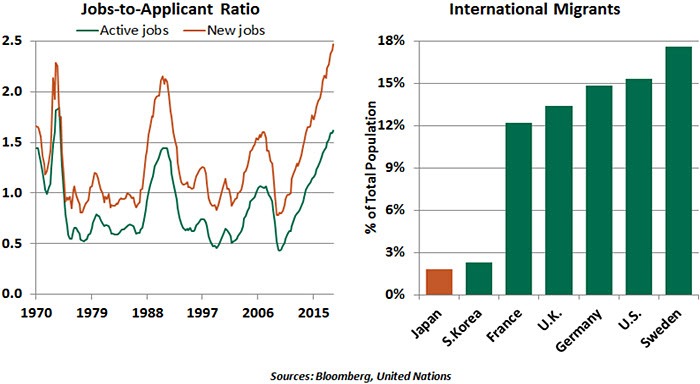

Japan is facing severe labor shortages because of an aging population. The active jobs-to-applicant ratio is hovering above 1.5, a level unseen since the mid-1970s. To address the situation, the Japanese government is taking several steps.

First, Japan hopes to attract half a million foreign workers to the country by 2025. The focus is on filling shortages in five relatively low-skilled sectors: agriculture, hotel, nursing care, construction and ship building.

The number of foreign nationals living in Japan has risen over the past 15 years, but their share in the total population remains the lowest among major developed economies. International migrants currently account for only 1.8% of the total population in Japan (up from 1.3% in 2000), compared to 15.3% in the United States, 14.8% in Germany and 13.4% in the United Kingdom.

Attracting outside help may not be difficult, but making them feel welcome might be harder. Language and cultural barriers are still present, and migrants will not be allowed to bring their families along. Still, this represents progress.

Second, the Japanese government is seeking to make its labor market more dynamic. Japan has a “job for life” system, under which annual pay raises are based almost solely on seniority. When an employee leaves a firm, irrespective of skills, he or she tends to start at the bottom of the salary structure. Though this system offers a high degree of job security, it discourages the kind of healthy turnover in which workers move to areas of greatest opportunity. It also hinders start-up ventures.

Third, there is a drive to generate faster increases in compensation. Despite chronic labor shortages, real wages in Japan have only risen about 0.5% over the past year. Faster wage growth and the additional spending it would support could help Japanese inflation approach the 2% target sought by the Bank of Japan.

Digging deeper, the data shows that the wage increases have largely been concentrated in the part-time sector (non-regular employees) instead of the full-time (regular) workers that currently account for about 60% of the workforce (down from over 70% about 15 years ago).

The rigidity of Japan’s wage system (discussed earlier) is something of a hindrance. Many firms prefer to pay one-off bonuses instead of raising base pay, a tactic that was employed earlier this summer. According to the Reuters Corporate Survey earlier this year, more than half of Japan’s firms had no plans to raise base pay, even as Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and the Japan Business Federation (Keidanren) were seeking a 3% wage rise.

Though the lifetime employment system remains the key hurdle, work-style reforms have also gained attention. The work reform bill (passed in June) relies on three arrows of its own: it puts a cap on overtime work (one in 10 workers puts in 60 hours or more per week in their main jobs), it requires equal treatment for part-time and full-time workers (part-time employees earn just over half of what full-time workers make), and it exempts skilled

Though the lifetime employment system remains the key hurdle, work-style reforms have also gained attention. The work reform bill (passed in June) relies on three arrows of its own: it puts a cap on overtime work (one in 10 workers puts in 60 hours or more per week in their main jobs), it requires equal treatment for part-time and full-time workers (part-time employees earn just over half of what full-time workers make), and it exempts skilled

professionals with high wages from working hour regulations.

Finally, Japanese policies also have become progressively more supportive of women’s labor market engagement. The participation rate of prime-age women in Japan now exceeds the average for the member countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (Female labor force participation in Japan is now higher than it is in the United States.)

The imperative of labor market reform in Japan has long been hindered by cultural mores and workplace traditions. Making change will be a protracted process. But at least the process is underway, and it seems to be gathering momentum.

Open, and Shut

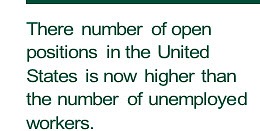

The American labor market has surprised most forecasters. On average, 215,000 positions have been created every month this year, an especially robust result for the tenth year of economic expansion. Given the retirement wave created by the baby boom generation, economists believe that job creation of about 100,000 per month is sufficient to keep the unemployment rate constant.

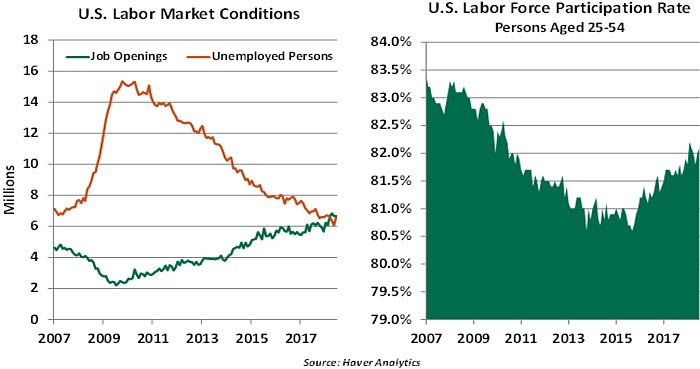

The future looks very promising, as well. The Bureau of Labor Statistics provides a monthly Job Openings and Labor Force Turnover Survey (JOLTS). The most recent report showed the highest number of available positions in 17 years. Total openings actually exceed the number of people who are categorized as unemployed.

Encouragingly, the strength of the American job market has drawn a number of workers back into the labor force. Those aged 25 to 54 years old have been a focal point for policy makers, as this cohort is typically past their schooling and some distance from retirement. Labor force participation among this very large group fell by 2.5% from 2008 to 2015, but has rebounded nicely since then. Tapping this reservoir of labor supply has helped to limit wage gains, which remain well below past expansion peaks.

Encouragingly, the strength of the American job market has drawn a number of workers back into the labor force. Those aged 25 to 54 years old have been a focal point for policy makers, as this cohort is typically past their schooling and some distance from retirement. Labor force participation among this very large group fell by 2.5% from 2008 to 2015, but has rebounded nicely since then. Tapping this reservoir of labor supply has helped to limit wage gains, which remain well below past expansion peaks.

Despite the plethora of available positions, those still jobless may not be able to take advantage of them. Skills and/or geography may not align, and the level of compensation may not be enough of an enticement. Sadly, there are an estimated two million Americans who are addicted to opioids; their path back to the labor market is a challenging one.

It has been gratifying to see such robust employment gains, which have become so widespread. And modest wage growth has helped to contain inflation. But sustaining this ideal combination may become more difficult in the months ahead.

northerntrust.com

Information is not intended to be and should not be construed as an offer, solicitation or recommendation with respect to any transaction and should not be treated as legal advice, investment advice or tax advice. Under no circumstances should you rely upon this information as a substitute for obtaining specific legal or tax advice from your own professional legal or tax advisors. Information is subject to change based on market or other conditions and is not intended to influence your investment decisions.

The information herein is based on sources which The Northern Trust Company believes to be reliable, but we cannot warrant its accuracy or completeness. Such information is subject to change and is not intended to influence your investment decisions.

Recommended Content

Editors’ Picks

USD/JPY holds near 155.50 after Tokyo CPI inflation eases more than expected

USD/JPY is trading tightly just below the 156.00 handle, hugging multi-year highs as the Yen continues to deflate. The pair is trading into 30-plus year highs, and bullish momentum is targeting all-time record bids beyond 160.00, a price level the pair hasn’t reached since 1990.

AUD/USD stands firm above 0.6500 with markets bracing for Aussie PPI, US inflation

The Aussie Dollar begins Friday’s Asian session on the right foot against the Greenback after posting gains of 0.33% on Thursday. The AUD/USD advance was sponsored by a United States report showing the economy is growing below estimates while inflation picked up.

Gold soars as US economic woes and inflation fears grip investors

Gold prices advanced modestly during Thursday’s North American session, gaining more than 0.5% following the release of crucial economic data from the United States. GDP figures for the first quarter of 2024 missed estimates, increasing speculation that the US Fed could lower borrowing costs.

FBI cautions against non-KYC Bitcoin and crypto money transmitting services as SEC goes after MetaMask

US FBI has issued a caution to Bitcoiners and cryptocurrency market enthusiasts, coming on the same day as when the US Securities and Exchange Commission is on the receiving end of a lawsuit, with a new player adding to the list of parties calling for the regulator to restrain its hand.

Bank of Japan expected to keep interest rates on hold after landmark hike

The Bank of Japan is set to leave its short-term rate target unchanged in the range between 0% and 0.1% on Friday, following the conclusion of its two-day monetary policy review meeting for April. The BoJ will announce its decision on Friday at around 3:00 GMT.