Financial system showing signs of strain

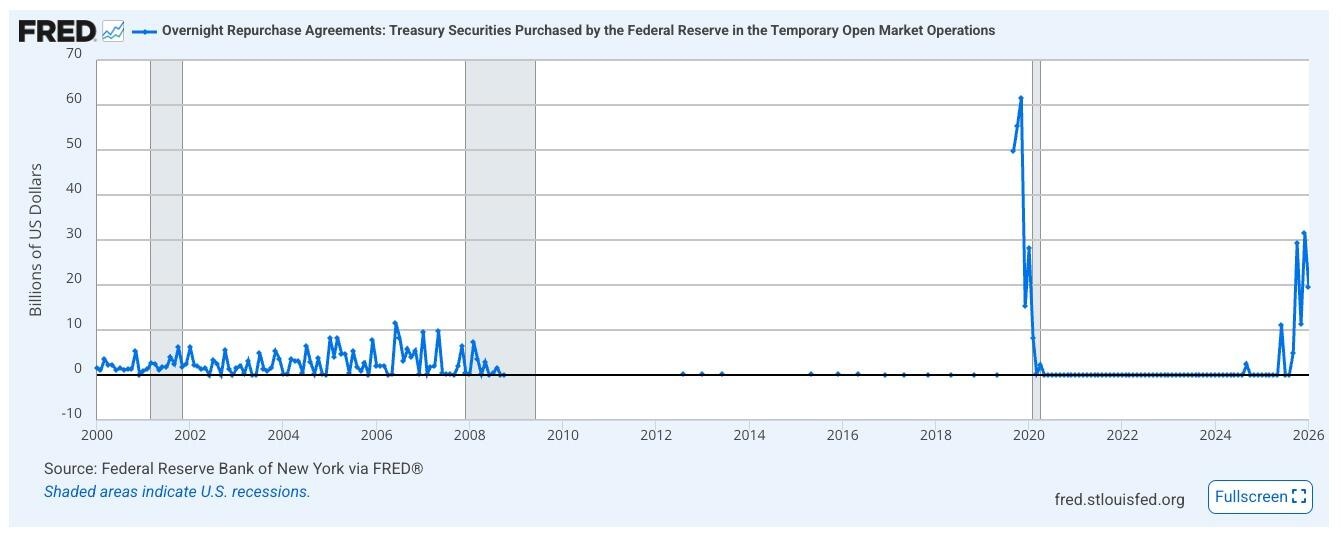

Repo operations at the Fed on the last day of 2025 signal growing stress in the financial system, similar to the setup we saw in 2019.

Banks and other financial institutions borrowed $74.6 billion from the New York Fed’s Standing Overnight Repurchase (repo) Facility on the final day of 2025. The last time we saw this kind of a spike in repo operations was in the months before the COVID-19 pandemic, as the stock market was tanking and the economy was going into spasms after the central bank began trying to “normalize” interest rates in the wake of the Great Recession.

Repurchase operations are an important aspect of the banking system. The repo market enables banks to borrow cash for a very short term to maintain liquidity and meet daily financing needs. In a repo trade, a financial firm puts up Treasurys and other “high-quality” securities as collateral for a short-term loan. The firm repurchases the bonds paying a nominal rate of interest, usually within 24 hours.

On Dec. 31, banks and other financial institutions put up $31.5 billion in Treasuries, along with an additional $43.1 billion in mortgage-backed securities to secure overnight loans.

Repo operations typically occur among private entities based on the market interest rate. A rise in the repo rate implies a shortage of available short-term cash.

According to Reuters, the general collateral (GC) repo rate on the open market was about 3.9 percent early Wednesday. That was higher than the Fed repo rate of 3.75 percent. This spread incentivized firms to borrow from the Fed at a cheaper rate.

In effect, the Fed’s repo facility functions as a liquidity backstop.

Between May 2020 and August 2024, the Fed’s repo facility was scarcely used. That doesn’t mean there were no repo operations. They were just facilitated through private lenders. When repo volumes at the Fed facility spike, it usually implies that the private repo supply isn’t meeting the market’s needs at reasonable interest rates.

There was a small spike in the use of the Fed’s repo facility in September 2024, before it began to climb in June ’25 as the second quarter ended.

Repo activity often jumps at the close of a quarter because the big banks and dealers that normally intermediate operations temporarily become balance-sheet-constrained as they make their financial position look as strong as possible. Meanwhile, other financial entities still need access to short-term.

This year-end spike in repo operations is notable due to its high volume. As noted, we haven’t seen this much activity in the Fed repo facility since September 2019.

The mainstream financial media downplayed the Fed repo spike. Reuters reported, “Most expect Wednesday's borrowing surge will dissipate over the coming days as more normal trading conditions reassert themselves.”

However, firms had already posted $19.5 billion in Treasuries at the facility as of January 3, 2026.

QE is back

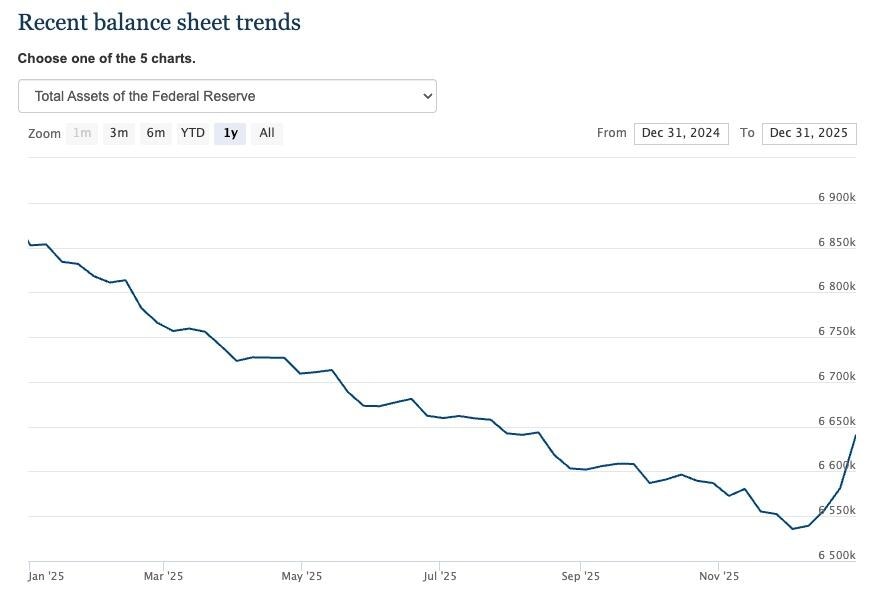

Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve fulfilled its promise to restart quantitative easing (QE). Of course, they’re not calling it quantitative easing, but the effect is the same.

The Fed’s balance sheet bottomed on December 3 at $6.54 trillion. At its December meeting on Wednesday, December 10, the Fed announced that it would purchase $40 million in Treasury Bills on Friday (Bills are short-term Treasuries that mature in one year or less). From that point, purchases will “remain elevated for a few months” before they are “significantly reduced.”

Since then, the balance sheet has increased by $104.8 billion.

This is, by definition, inflation.

What are these Fed monetary mechanizations telling us?

While the mainstream generally insists that these operations are only meant to keep the financial system's “plumbing” clear, and that it's no big deal, it more likely signals deep stress in the system due to higher interest rates.

Simply put, an economy and financial system addicted to easy money can’t function in a higher-rate environment. Especially when that monetary policy has incentivized a Debt Black Hole. That’s why so many people are desperate for rate cuts despite persistently high inflation.

We’ve seen this show before.

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed bought more than $3.5 trillion in bonds via QE, and banks built up massive cash reserves at the Fed. That level peaked at around $2.8 trillion and began to drop in 2015, when the Fed started raising interest rates. The decline in reserves accelerated when the central bank began its balance sheet reduction operation in October 2017, and more aggressively hiked rates.

In the fall of 2018, the economy began to crack under the Fed’s monetary tightening. The stock market tanked, and the economy got wobbly. The Fed was forced to cut rates three times in 2019 and resume QE, just like today.

The pandemic bailed the Fed out in 2020, allowing the central bank to slash rates to zero and take QE to unprecedented levels. This kicked the can down the road, giving the easy money-addicted economy a surge of its preferred drug, and keeping the inevitable crash at bay.

Now, we’re starting to see the same pattern playing out once again.

Analysts have noted that as the balance sheet shrank in March 2022, with quantitative tightening, repo volatility reappeared, first on month/quarter-ends and then more broadly. This signals that reserves are getting closer to "less-than-ample."

This is exactly why the Fed has pivoted back to QE.

It remains unclear if these modest moves can stabilize the financial system, and if so, for how long. Thanks to the pandemic, the scenario never played out in 2020. Were it not for the massive monetary injection during COVID, the economy would have likely gone into a deep recession to cleanse the monetary excesses of the Great Recession. Instead, the pandemic allowed the central bank and the government to double down with stimulus, delaying the inevitable.

In other words, the economy never reckoned with the monetary malfeasance of the Great Recession era. Instead, the Federal Reserve and the government doubled down and added more fuel for the inevitable fire.

The reality is that the economy has to have its easy money drug. Without it, the addict goes into painful withdrawals.

The Fed (the pusher) has begun to dribble the monetary heroin into the addict’s veins. The problem is, over time, it takes more and more of the drug to maintain the high. Eventually, the druggie will OD.

No matter how this plays out, we’re looking at an increasingly inflationary environment. The money supply is already growing at the fastest rate since July 2022, in the early stages of the tightening cycle, and the pace of money creation will increase as the Fed continues QE (without calling it QE). We will also likely see additional rate cuts. That means you can look forward to the purchasing power of your dollar declining even more rapidly.

Plan accordingly.

To receive free commentary and analysis on the gold and silver markets, click here to be added to the Money Metals news service.

Author

Mike Maharrey

Money Metals Exchange

Mike Maharrey is a journalist and market analyst for MoneyMetals.com with over a decade of experience in precious metals. He holds a BS in accounting from the University of Kentucky and a BA in journalism from the University of South Florida.