Tracking the Coronavirus, Evaluating the Ease of Doing Business, Ending Negative Rates in Sweden

Summary

-

More on the Asian Contagion

-

Rating the Ease of Doing Business

-

Sweden Tries Being Positive

I spent a good portion of the last two weeks traveling along the west coast of North America. The atmosphere in the airplanes and airports was cautious. Many were wearing face masks, jumbo dispensers of hand sanitizer were everywhere, and heads turned nervously at every sneeze and cough.

Sneezes and sniffles are not at all uncommon in early February. Nor is influenza, which infected an estimated 35 million Americans last year. (Sadly, about 34,000 of those patients did not survive, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.) But this year, fear of the coronavirus has people around the world on edge. While we don’t anticipate significant damage to global growth, the spreading sickness and the response it has prompted could create a more serious economic affliction.

When an outbreak of disease occurs, cases initially escalate rapidly. This trajectory can generate considerable alarm, which persists until officials demonstrate control. As events unfold, epidemiologists monitor an “r-factor,” which captures the number of people that are likely to be infected by a given carrier. To reduce the r-factor, public health officials use preventative measures like quarantine.

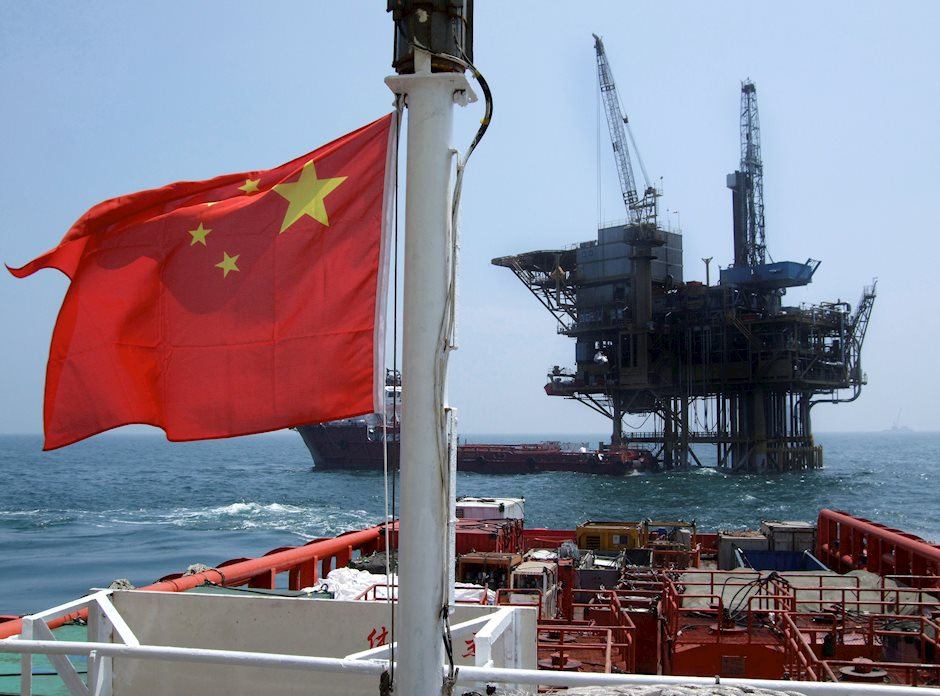

Chinese officials have taken aggressive steps to contain the coronavirus. They have closed down entire cities, limited travel and closed workplaces. While well-advised from a medical perspective, this strategy has the side effect of initiating an economic r-factor. With the movement of products and people restricted, businesses across the globe are hindered.

Those markets linked most closely to China economically are the ones facing the biggest impairment. Hong Kong, which was already in recession in the wake of stress with Beijing and the contraction of trade flows, now has another significant challenge to deal with. South Korea and Japan import substantial volumes of components from Chinese factories, and have been forced to slow or stop their own assembly lines. (Japan must also be sweating over how the epidemic might affect the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, which are scheduled to begin in late July).

Even countries further from the epicenter of the outbreak have been affected. Providers of commodities used in Chinese factories have seen orders reduced and prices fall. Crude oil prices have fallen by about 15% since the start of the year. The inability to get parts from China has idled plants in Europe and North America. Global manufacturing, which has been struggling amid trade frictions, is likely to remain in retreat for a good portion of 2020.

“Actions to contain the virus inhibit economic activity.”

On the demand side, Chinese consumers have been put into limbo. The Lunar New Year interval usually witnesses the peak of annual spending in many Asian countries, so the outbreak came at an especially bad time. Stores selling wares from domestic and Western providers have closed due to a lack of traffic. Chinese tourism, which has burgeoned over the past decade (with Chinese tourists spending an estimated $279 billion annually in other countries) has slowed to a crawl.

Business interruption damages a company’s finances, and the finances of Chinese firms had been the subject of concern even before the coronavirus appeared. China’s corporate sector has taken on a substantial amount of leverage during the past decade, a good portion of which is owned by retail investors. A prolonged battle with the epidemic could cause a series of defaults and compromise financial stability.

The interruption in Chinese factory production will complicate delivery schedules, which have been engineered to very tight tolerances. Apparel and computer makers are already concerned about supplies for the fall season. Longer-term, the vulnerability exposed by the coronavirus may provide another reason for global manufacturers to consider alternate sourcing. Trade frictions between the United States and China have already prompted a re-examination of global supply chains; the outbreak could add momentum to this effort.

Analysts trying to anticipate the progression of economic impairment caused by the coronavirus have leveraged past pandemic episodes, like the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003. But each pathogen is different, as is its potential to interfere with commerce. China had only recently entered the World Trade Organization in 2003; the scale of its economy and its linkages to others through supply chains has mushroomed since then.

Our central expectation is that preventative measures will take the worst-case outcomes off the table. Medical officials are expressing optimism that the virus and its consequences will be contained. In this optimistic scenario, output would be deferred by the coronavirus, but not lost. Most forecasters have downgraded their estimates of global growth in the first half of the year, but have compensated by adding to their projections for the second half.

“We expect the virus to be contained, but the outbreak presents substantial downside risk.”

The message from markets on the coronavirus has been mixed. Equity markets in the U.S. continued their upward march without much apparent concern. But Asian stock markets have slumped. Safe haven currencies and safe investments are in heavy demand. The U.S. dollar has been exceptionally strong, and U.S. interest rates have fallen. The American yield curve is flirting with inversion again, but we do not see this as a sign that recession is imminent.

To provide a cushion, Chinese officials have injected substantial amounts of liquidity into Chinese markets and reduced the reserve ratios that banks are required to meet. The U.S. Federal Reserve has mentioned the coronavirus as a situation it is watching, but the threat is not yet severe enough to prompt a U.S. interest rate cut.

Ironically, lowering the epidemiological r-factor for the coronavirus increases the economic r-factor, at least in the short-term. For now, it appears that this is a short-term concern that will not create lasting economic damage. But if the outbreak escalates, the global economy may fall seriously ill.

Easier Said Than Done

Entrepreneurs and business leaders around the world will tell you that it isn’t easy to start and run a business. There are forms to file, fees to be paid, loans to be drawn, inventory to purchase. But these steps are easier to take in some countries than others. The World Bank’s ease of doing business index is an ambitious effort to compare the experience of running a business across nations. This effort has prompted the adoption of business-friendly reforms and can help to steer investment decisions.

Compiling the index is no small task. Requirements and procedures are usually available freely, but actual experiences can differ from what is laid out in statute. World Bank researchers don’t merely track policy at arm’s length. They visit with business owners, lawyers and accountants worldwide to see how countries’ processes work in practice.

Comparisons are made across the following broad categories:

Starting a Business: The survey rates the effort, expense, and complexity of establishing a new business. Among the factors considered are constructing buildings, obtaining electric service and registering property. In leading countries, filing paperwork for a new venture will cost less than 1% of average annual per-capita income and can be completed in less than a week. Meanwhile, entrepreneurs in Suriname can expect to pay nearly a year’s income and wait two months just to file a new business application.

Running a business: The survey assesses the challenges businesses face in obtaining credit and conducting import and export transactions. As recent trade tensions have reminded us, international trade can be quite complex, even under supportive regimes. The ability to send and receive products and payments across borders is a clear proxy for a country’s accommodation for its businesses.

Governance: The survey evaluates tax rates, the complexity of the tax system, protections for investors, the legal structures for enforcing contracts, and creditors’ ability to recover losses from an insolvent business.

The World Bank index compiles all of these into a score, allowing a ranking of countries. Nations can make policy changes to improve their standing: the less red tape and lower fees required for business activity, the more business will get done. But that is not to suggest a free-for-all would be deemed optimal. The index rewards countries that require complete financial disclosures and grant recourses for payment to creditors. Low tax rates alone are not sufficient to get a leading score.

Countries that score well should come as little surprise: Their reputations precede them as countries with high productivity, diverse economies and well-functioning governments. Countries that struggle are conversely burdened by unrest and war. 2020’s worst scores came from Somalia, Eritrea, Venezuela, Yemen and Libya. These countries have greater and more immediate problems than paperwork and tax collection.

“The World Bank recognizes business-friendly reforms.”

The index is most notable for giving developing nations an opportunity to demonstrate improvement. Several growing economies have had their recent reforms recognized by substantial improvements in their ease of doing business ranking. It can be difficult to climb to the top of a list of 180 countries, but an improved rating is direct evidence of successful reform. Increased liberalization in India stands out as an example of effective policy.

Naturally, the ease of doing business index has limitations. Its focuses on experiences in major cities and does not give a full view of each country. Comparing company structures and fees requires some discretion, and under-the-table “facilitation fees” often go undisclosed. But as a measure of economic potential, the index helps us to put national growth in context.

Zero Can Be A Positive Number

The latest Riksbank interest rate hike was supported by an inflation rate close to its target, as well as growing concerns about the implications for the economy from sub-zero rates. An overheated housing market caused by negative interest rates and a shortage of housing was also on governors’ minds. The removal of negative monetary policy will reduce pressure on the nation’s financial sector.

The Riksbank has its critics. The Swedish economy is slowing in the face of weak domestic and external demand. The composite Purchasing Managers’ Index reached a multi-year low, and consumer confidence remains weak by historical standards. Falling commodity prices will soften inflation. Business sentiment is painting a gloomy picture, and with the coronavirus disrupting global supply chains and trade flows, the export focused Swedish economy could slow further. It seems like a bad time to tighten policy.

But proponents might question whether the Riksbank’s actions should be viewed as more restrictive. Negative rates have had adverse side effects, including weaker bank profitability and the promotion of excessive risk-taking. Moving back to zero realigns incentives to lend and invest in a manner that should promote more healthy economic growth.

“In Sweden's case, raising interest rates may be viewed as an easing.”

Developments in Sweden will be closely watched in Frankfurt, the headquarters of the ECB, where many think negative interest rates have been counterproductive, hindering lending and saving. As ECB President Christine Lagarde takes the bank through its current strategic review, she may use Sweden as a reason to become more positive.

Author

Northern Trust Economic Research Department

Northern Trust