New data confirm Irish economy now on improving path.

Jobs and property markets recovering.

Markets becoming optimistic that ‘Tiger-lite’ can return.

Bulk of heavy lifting on public finances now completed.

Debt dynamics to benefit from stronger growth trajectory.

‘Draghi Put’ has been hugely helpful to positive sentiment.

Ratings upgrades confirm healthier outlook.

Irish bond market has priced in much of the good news.

The sea‐change in sentiment towards Irish government bonds continued through the first half of 2014, meaning Ireland’s exit from its EU/IMF assistance programme has gone very well even without the ‘safety net’ of an official credit line. As diagram 1 shows, the 10 year yield spread versus Germany ended the first half of the year at 110 basis points—around 40 bps lower than it began the year and a full 120 bps below mid‐2013 levels.

Bond performance reflects many factors

Several factors encourage the view that Ireland can return to stronger growth and reduce public debt levels, thereby sustaining a return to market funding without particular difficulty. In turn, this supports the Irish bond market.

Importantly, we think these supports should remain in place for some significant time.

The first and arguably most important factor helping sentiment towards Ireland is a broader sea‐change in investor thinking. Since mid‐2012 there has been a marked easing in systemic fears about the Euro area. Investors are confident that the ECB will do ‘whatever it takes’ both to counter existential risks to the single currency and, within its mandate, to support a recovery in economic activity. This so‐called ‘Draghi Put’ has contributed hugely to a reduction in risk premia.

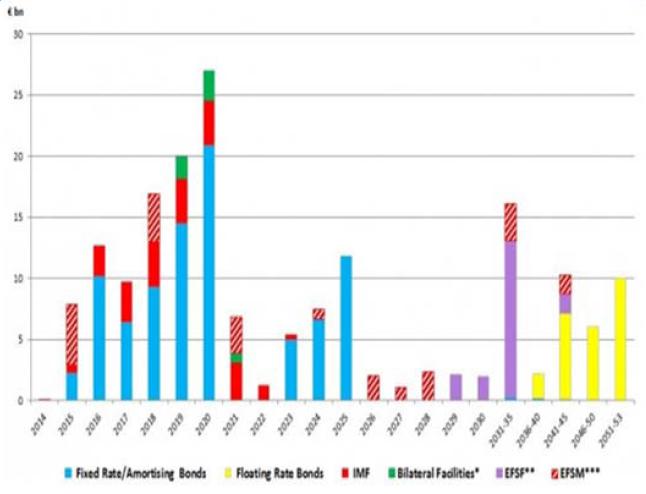

A second consideration is that the deal reached on Ireland’s promissory notes early in 2013 and the subsequent extension in the maturity of loans from the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and the European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism (EFSM) materially improved the sustainability of Ireland’s public finances.

The promissory note deal reduced funding requirements by some €20bn for the next decade while seven year extensions to the maturity of EFSF and EFSM loans further enhanced the maturity profile of Irish government debt.

A third and perhaps distinguishing element in the case of Ireland has been increasing confidence in the capacity of the economy to return to a comparatively strong medium term growth path. While this won’t prompt a return of the Celtic Tiger and won’t be credit‐driven, it may lead to a ‘Tiger‐lite’ era in coming years where Irish growth outperforms most of Europe. For this reason, we examine the emerging recovery in some detail in this note but, as usual, we begin by describing some key features of the Irish bond market at present.

Bond ‘Fundamentals Are Encouraging

Irish Government debt now stands at roughly €210bn in gross terms. The net figure is notably smaller as cash and other financial assets that were built up initially as a ‘war chest’ and more recently to ensure a smooth return to market funding now amount to about €27bn. Some €23bn of Ireland’s debt is funded by State savings schemes and short term debt while €67bn is financed through EU/IMF assistance programmes. So, total outstanding debt on the Irish government bond market amounts to €112bn or some 54% of Irish GDP.

Irish Government bonds comprise three types of instruments. The most important are conventional government bonds (IGB’s) with 11 benchmark issues carrying maturities ranging between 2015 and 2025. This is the largest element of the bond market amounting to just under €86bn.

A second category is Irish amortizing bonds (IABs). These are longer‐dated amortizing bonds issued specially for the Irish pension industry. The amount involved is tiny at just under €1.4bn. This highlights the relatively low participation of the domestic pension industry in the Irish market largely because the Euro area rather than Ireland is designated the ‘home’ market. More recently, ratings considerations have also limited this segment of the market.

The remaining €25bn of bonds comprises long term floating rate notes that derive from the restructuring of the promissory note deal in early 2013. Promissory notes were the mechanism initially used by the Irish government to pay €31bn of Anglo Irish/INBS bailout costs. €25bn of promissory notes still outstanding in early 2013 was replaced with a portfolio of €25bn long term floating rate government bonds maturing between 2028 and 2053. This switch has reduced funding needs through the next decade by about €20bn or about 1.5 % of GDP annually.

These bonds were placed with the Central Bank in exchange for the promissory notes and, according to the Department of Finance, they will be sold over time but ’only where such sales are not disruptive to financial stability’. The Department also indicated that a minimum of €0.5bn per annum of these bonds would be sold between 2014 and 2018, €1bn per annum between 2019 and 2023 and €2bn per annum from 2024. A somewhat faster pace of sales is likely as conditions allow in order to allay some European concerns that the new mechanism constitutes monetary financing.

As diagram 2 shows, the maturity structure of Irish Government debt is comparatively favourable. The nearterm funding outlook has been further improved by bond exchanges and buybacks by the NTMA. There are no further redemptions this year and only two small redemptions– 4.5% Feb2015 IGB (€2.23bn) and 8.25% Aug2015 IGB (€0.07bn) as well as €0.7bn of IMF loan repayments due next year.

Ireland’s liabilities under the EU/IMF programme amount to €64.59bn. As noted above, maturities of EFSM/EFSF debt were extended in 2013. The weighted average life of EFSM loans (€21.7bn) increased from 12.5 years to 19.5 years and for EFSF loans (€16.14bn) to 20.8 years. The weighted average life of bilateral loans (€4.87bn) and IMF loans (€21.88bn) is 7.5 years, with the first IMF redemption in 2015 (of around €0.7bn).

While regular short term auctions have resumed and the NTMA will continue to look for switching opportunities in relation to longer dated issues, an important focus for the next year or two will be to gradually reduce current cash balances of around 13% of GDP to help reduce the debt/GDP ratio.

Ireland is fully funded for this year and had raised €6.5bn of a planned €8bn for 2015 by early May. Next year’s deficit is expected to be around €5.2bn. In addition, the NTMA holds a significant liquidity buffer (cash and short term investments of €22.4bn at the end of May). Ireland is expected to offer some €8bn of long term bonds in 2015 and about €12bn per annum from 2016. Ireland’s very strong funding position was an important consideration in the well‐received decision to return to market funding without an official credit line.

The next real Irish ‘funding cliff’ doesn’t come until 2019‐ 2020, when relatively large amounts of IMF funding and bilateral loans are due to be repaid and there are also significant bond redemptions. These various elements combine to produce total maturities of €20bn in 2019 and €27bn in 2020. So, the NTMA should be able to ensure the persistence of a favourable funding profile for the foreseeable future. This focus to the NTMA’s operations is seen in this week’s offer to buy back the 2016 4.6% bond or to switch it into the 2023 3.9% bond.

Important Ratings Upgrades In 2014

Market appetite for Irish Government debt has remained very strong. Bids at the early May 10 year auction were 2.8 times the amount sold. Sentiment has been assisted by a sequence of positive ratings actions through the first half of 2014. In January, Moody’s upgraded Ireland to investment grade and followed this with a further two notch upgrade to Baa1 in May, noting that growth momentum would ‘speed up ongoing fiscal consolidation’ and put debt on ‘a steeper downward trajectory than previously anticipated’. A further consideration was ‘a very sharp reduction in offbalance sheet exposures’ as the ’recovery in the property market has resulted in a considerable recent reduction in government contingent liabilities’. Reflecting broadly similar influences, S&P became the first major ratings agency to restore an A rating to Ireland’s sovereign debt in early June. Ireland is currently rated A‐ at S&P, Baa1 at Moody’s and BBB+ at Fitch. The outlook of the ratings is stable at Moody’s and Fitch and positive at S&P.

Spreads on 2020/2023 IGBs have fallen sharply in the past six months and now hover around 100 bps over mid‐swap in the ten year area and just 30bps in the seven year area. As recently as December 2013, these were both trading in the region of 150bp over mid‐swap. Irish debt currently trades richer (in ASW spread terms) than Italian and Spanish debt. We expect that this will continue.

Strong Growth Prospects

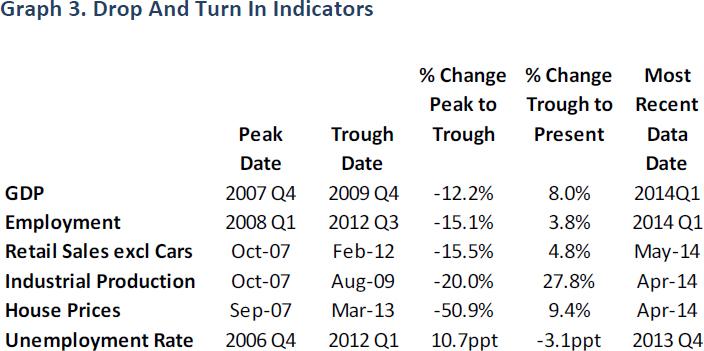

Recent revisions suggest the Irish economy is on a stronger trajectory than previously thought. They also show it to be somewhat larger in size than previous estimates had indicated. Since late 2012, evidence of a clear if uneven improvement in Irish economic conditions has helped support the bond market. However, this has not been a uniform progression. As table 3 below indicates, the most commonly watched short term indicators emphasize differences in the intensity of the downturn and the pace of recovery across various sectors.

Between 2010 and 2012, positive Irish economic signs were largely concentrated on the export sector, particularly exports by multinational companies based in Ireland. Ireland’s multinational sector is almost exclusively focussed on export markets and was little affected by the Irish Governments austerity programme.

A 4.1% drop in goods exports in 2013 owes something to weak export markets, but it also reflects an outsized impact from the ending of patents on some pharmaceutical products produced in Ireland. While this development had a major impact on the reported volume of merchandise exports and depressed GDP, the specialized nature of the production of these pharmaceuticals means the effects of this development on employment or domestically sourced inputs have been very limited.

The fact that Ireland was willing and able to deliver consistently on its EU/IMF programme commitments without major damage to social cohesion meant that there was little reputational damage from the recent crisis within its multinational sector. Instead, a significant improvement in Irish competitiveness in recent years contributed to a record number of new foreign direct investment projects in 2013. Together with signs of healthier demand conditions in important trading partners such as the US and the UK. This suggests Irish export growth can move onto a stronger trajectory in coming years. The relatively large size of Ireland’s export sector means it will remain the key driver of economy‐wide growth.

The small and open nature of the Irish economy makes export performance central to determining a sustainable growth trajectory. However, domestic spending tends to be ‘richer’ in terms of jobs and tax revenues. As graph 3 indicates, an extended and uneven ‘bottoming‐out’ in domestic spending has been underway for some time.

Signs of an improvement in domestic spending are particularly notable because of the intensity of the downturn in this area. Compared to the pre‐crisis peak, domestic spending fell by 23%, twice the size of the drop in Irish GDP. This particular weakness was associated with severe declines in employment, incomes and domestic asset values. When account is taken of cumulative Budget changes to tax and benefits as well as the impact of job losses and cuts in earnings, the after tax incomes of Irish households fell by around 14% from their 2008 peak.

The crisis also prompted a significant ‘internal devaluation’ through a reduction in Irish costs. Official wage data put weekly earnings through 2013 around 3% below 2008 levels and preliminary data for the first quarter of this year suggest a softening trend remains in place at the aggregate level although divergent trends are becoming evident across sectors.

As recovery progresses, pent‐up demand for consumer durables and an easing in precautionary saving should help sustain growth in Irish household spending. A significant turn in employment, incomes and sentiment should also boost consumer spending which we see increasing by around 1% in 2014 and 2% in 2015.

Jobs And Property Markets Showing Strength

Numbers at work have grown for five quarters in a row and survey indicators suggest new hiring may be strengthening further. The pace of job gains may seem surprising compared to the trend in the main activity indicators, possibly suggesting some ‘overshooting’ in terms of the scale of job losses through the downturn. Diagram 4 indicates the intensity of the drop in numbers at work and the associated rise in the unemployment rate as well as implying an improvement in labour market conditions has taken hold. We see employment growth in 2014 of around 2%, marginally slower than last year’s exceptional 2.4% pace.

The rise in numbers at work together with net emigration means the unemployment rate fell from its early 2012 peak of 15.1% of the labour force to 11.6% in mid‐2014.

Unemployment should ease further through coming years. Indeed, on the current trajectory, the unemployment rate could drop below 10% by late 2015. Even on more cautious assumptions, the prospects for employment and unemployment now look much better than envisaged a year ago.

Alongside the improvement in the jobs market, the clearest indication of healthier conditions in the broader Irish economy of late is the pick‐up in prices and transactions in the property market. As diagram 5 shows, residential and commercial property market trends have been very similar reflecting their link to broader economic conditions. The turn in the property markets is obviously important to the general economic outlook and, from a bond market perspective, it is also important in terms of banking sector risks and related contingent liabilities of the Government.

The turn in property market conditions is illustrated by the successful sale of a €13bn property loan portfolio stemming from the liquidation of the IBRC (It had been expected that many of these loans would be transferred to NAMA for a possibly lengthy work‐out). Commercial property values have been supported by strong overseas interest and a significant shortfall of prime properties reflecting a strong pipeline of foreign direct investment into Ireland and a dearth of new building.

Residential property values rose by 10.6% in the year to May 2014 and transactions were nearly a third higher in the first five months of this year than in the same period of 2013 albeit from a very low base. This mirrors a similar but earlier change in the residential rental market where official data show rising rents since early 2011.

The emerging positive momentum in property prices clearly reflects confidence in the broader economy. In addition, the scale of price declines through the downturn has significantly improved affordability and other valuation metrics (the ratio of residential prices to incomes has fallen below the long term average). As such, the current buoyancy reflects pent‐up demand underpinned by solid demographics. With little new construction in recent years, relevant supply in key market segments is quite limited at present and probably for some time to come.

An improving Irish economy in coming years should support housing demand while the pace of ‘normalisation’ of ECB policy rates does not seem threatening. In turn, this should limit any risk that the process to resolve troubled Irish mortgages, now moving towards an advanced stage (on foot of quantitative Central Bank targets for sustainable solutions for loans in arrears), might have adverse implications for the Public finances.

Public Finances On The Mend

The ability and willingness of successive Irish Governments to take difficult measures to tackle major problems in the public finances has been a notable positive for the bond market.

Of an agreed fiscal adjustment totalling 20% of GDP, measures amounting to some 19% of GDP were implemented between 2009 and 2013, leaving a small if not insignificant adjustment to be completed. The Government is firmly committed to meeting the target deficit of 3% of GDP by 2015. The key question relates to the amount of adjustment this might require, with estimates ranging from €1bn to €2bn. Our sense is that a number towards the lower end of this range is likely to be chosen.

A substantial and now quite lengthy adjustment process has reduced the primary deficit (i.e. the deficit excluding interest payments) by some 15 percentage points of GDP since 2009. While official forecasts envisage a primary balance this year, we think a small surplus—possibly about 0.5% of GDP may be reached. An improving economy should cause the primary surplus to meet official estimates of around 3% of GDP in the next couple of years.

The build‐up in Ireland’s public debt in recent years means related interest payments are expected to be just over 4% of GDP in 2014 and coming years. This implies the headline deficit will to around 4% of GDP in 2014 and below 3% in 2015. As the cumulative impact of adjustments and somewhat stronger economic activity take effect, a small Budget surplus is targeted for 2018.

Actions taken in recent years have resulted in lasting changes to taxes and public spending. There have been sharp increases in income taxes and indirect taxes and the introduction of a residential property tax. These changes should increase the future stability of a tax base exposed by the downturn. Similarly, Public spending cuts entailed a large drop in capital spending, cuts to public sector pay rates and pensions and reductions in most welfare benefit payments as well as limitations on entitlement. Successive governments also resisted any possibility of an increase in Ireland’s 12.5% corporation tax rate, thereby emphasizing the continuing importance of foreign direct investment to Ireland.

Although Ireland has successfully exited its EU/IMF programme, fiscal policy will remain constrained by Stability and Growth Pact requirements that initially entail a deficit of 3% of GDP by 2015 and subsequent improvements in the fiscal balance of 0.5% of GDP per annum to achieve a structural balance. Unless economic conditions are unexpectedly poor, these targets should not be particularly difficult to meet. Indeed, the Government has indicated a desire to ease the income tax burden somewhat but there appears little scope for significant fiscal stimulus in coming years.

Debt Dynamics Supported By Strong Growth Potential

The recent crisis caused an explosive increase in Irish government debt from 24% of GDP in 2007 to 116% of GDP at end 2013 as diagram6 indicates. Recent revisions to Irish National Accounts data have had a material and positive impact on the various fiscal ratios that use GDP as a denominator. For example, the 2013 deficit was reduced from 7.2% of GDP to 6.7% of GDP while the debt ratio was reduced from 124% of GDP to 116% of GDP.

When cash and other allowable assets are taken into account the net debt figure is reduced by some 25 percentage points to around 90% of GDP. An expected reduction in Government cash balances should mean the debt/GDP ratio declines by a couple of percentage points in 2014.

The longer term outlook for Ireland’s debt ratio will be shaped in part by constraints on fiscal policy noted above.

However, the performance of the Irish economy is likely to be the critical factor shaping the outlook for Ireland’s public finances and, by extension, the prospects for the Irish bond market. As diagram 5 makes clear, the ‘Celtic Tiger’ period saw a transformation of Ireland’s public finances on foot of rapid growth.

In the pre‐crisis years of 2003‐2007 rapid Irish growth was primarily driven by expansionary policy settings, immigration and an associated debt‐fuelled housing boom that proved to be unsustainable. The aftermath of the crisis will act as a constraining influence on growth through its implications for fiscal policy, credit growth and risk appetite. However, competitiveness has been improved, foreign direct investment is strong and demographics remain comparatively favourable (Ireland continues to have the highest fertility rate and the lowest old age dependency rate in the EU). In addition, the flexibility of the economy and social cohesion appear to be largely intact in spite of the intensity of the downturn.

We estimate Ireland’s potential real GDP growth rate to be in a range between 2.5 and 3%, for the period 2014‐2016 and expect it to run towards the upper end of this range between 2017 and 2025. This is notably less than the average annual growth rate between 1987 and 2007 (5.9%), but still substantially higher than elsewhere in the euro area and, as such, is supportive of the Irish bond market.

Outlook Depends On ECB As Well As Ireland

Notwithstanding the favourable economic backdrop now emerging, value in Irish bonds may be somewhat limited in absolute terms at present. The Irish market is probably best seen as a compromise in that it offers some additional yield while it is supported by the prospect of comparatively favourable economic and debt dynamics.

Much depends on the broader macro context, in particular, the performance of the Euro area economy and the related stance of ECB policy. If global bonds come to reflect expectations of a global recovery and an eventual normalisation of policy interest rates, Ireland’s current yield spread offers limited comfort in absolute terms although it may be well supported in relative terms.

Alternatively, in an environment where European growth remained sluggish and markets continued to speculate about a major ECB asset purchase scheme, Ireland’s recent policy track record and likely superior long‐term fundamentals would make Irish bonds look attractive. Of course, a markedly weaker Irish growth scenario might weigh on the capacity to continue fiscal adjustments and to fully resolve the housing market and banking crises.

Furthermore, the small size of the market can make it prone to transaction‐related volatility on occasion. This means the trend in Irish yields may be somewhat choppier than it has been in recent years.

This non-exhaustive information is based on short-term forecasts for expected developments on the financial markets. KBC Bank cannot guarantee that these forecasts will materialize and cannot be held liable in any way for direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this document or its content. The document is not intended as personalized investment advice and does not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold investments described herein. Although information has been obtained from and is based upon sources KBC believes to be reliable, KBC does not guarantee the accuracy of this information, which may be incomplete or condensed. All opinions and estimates constitute a KBC judgment as of the data of the report and are subject to change without notice.

Recommended Content

Editors’ Picks

AUD/USD remained bid above 0.6500

AUD/USD extended further its bullish performance, advancing for the fourth session in a row on Thursday, although a sustainable breakout of the key 200-day SMA at 0.6526 still remain elusive.

EUR/USD faces a minor resistance near at 1.0750

EUR/USD quickly left behind Wednesday’s small downtick and resumed its uptrend north of 1.0700 the figure, always on the back of the persistent sell-off in the US Dollar ahead of key PCE data on Friday.

Gold holds around $2,330 after dismal US data

Gold fell below $2,320 in the early American session as US yields shot higher after the data showed a significant increase in the US GDP price deflator in Q1. With safe-haven flows dominating the markets, however, XAU/USD reversed its direction and rose above $2,340.

Bitcoin price continues to get rejected from $65K resistance as SEC delays decision on spot BTC ETF options

Bitcoin (BTC) price has markets in disarray, provoking a broader market crash as it slumped to the $62,000 range on Thursday. Meanwhile, reverberations from spot BTC exchange-traded funds (ETFs) continue to influence the market.

US economy: slower growth with stronger inflation

The dollar strengthened, and stocks fell after statistical data from the US. The focus was on the preliminary estimate of GDP for the first quarter. Annualised quarterly growth came in at just 1.6%, down from the 2.5% and 3.4% previously forecast.